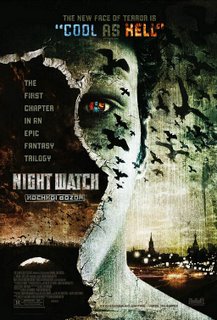

More specifically, MSN's pop-up window featured a review of Night Watch by Angela Baldassarre. I present her article below in its entirety:

Entertaining fantasy film

Night Watch (3 out of 5 stars)

Starring Konstantin Khabensky and Aleksei Chadov. Directed by Timur Bekmambetov.

Comparing Timur Bekmambetov’s “Night Watch” to Russian films of the past, you can’t help but notice a sea of change in Russian cinema. Whereas films like “Russian Ark,” “Burnt by the Sun” and “Prisoner of the Mountains” drew on Russian history and literature, “Night Watch” is inspired by comic books, video games, and fantasy films. And with audiences making “Night Watch” the #1 box-office movie of all time in Russia, it appears the nation is embracing the change.

The film rests on the premise that among regular humans live people called “Others” who have supernatural powers. These “Others” side with either the forces of light or the forces of dark. Centuries ago, after a cataclysmic battle, the two sides signed a truce. Since then, the day is the realm of the light forces, akin to angels, who protect the world from the dark forces that rule the night, who are essentially vampires. Move to modern Moscow, and enter Anton (Konstantin Khabensky), an unwitting “Other” who joins the “Night Watch” — a kind of supernatural police force. While in charge of saving a young boy from vampires, Anton upsets the balance of power and sets off a chain reaction of epic proportions. If you’re confused enough by the back-story, then the plot of the film, involving shape-shifters, a cursed woman and a vortex that threatens to break the truce between light and dark, might not be worth getting into.

But “Night Watch” is a film worth getting into. It obviously owes much of its mythology to “The Lord of the Rings,” with an art direction that resembles the bloody comic-noir of “Blade,” but director Bekmambetov injects dollops of original style — with the help of one of the biggest budgets in Russian film history. From his swooping camera, to ghostly computer effects, to video game sequences, and an ingenious flipbook animation sequence, “Night Watch” is cool and creative. As is the trend with films of this ilk, it’s heavy on atmospherics and chilly on emotion. Khabensky, in particular, is nearly a zombie in shaggy hair and sunglasses. One surprise is that given all the Other-worldly atmosphere (and requisite heavy metal score), “Night Watch” is light on action, something that might disappoint North American audiences. Yet the film does end in a sort of cliffhanger that certainly leaves room for further installments, and maybe more action to come.

“Night Watch” is an entertaining fantasy film, one that benefits from its Russian perspective while still feeling familiar enough for most fans of the genre. More importantly, Bekmambetov’s cultural coup may be a sign of cooler things to come in the stodgy former Soviet Union.

The principal reason for citing a complete movie review is clear enough: it happens to be one of the most blantantly stupid articles I have ever read. I know nothing about Miss Bald-ass-arre, but her iditiotic commentary gives me no desire to change this fact. I am fairly confident, however, that she happens to be a critic of Hollywood movies, rather than an actual film scholar. The latter implies a thorough understanding of the genre.

The former does not.

This author's mention of a "heavy metal" soundtrack that Night Watch supposedly uses is a tell-tale sign of the utterly oblivious nature of the rest of her review. Apparently generic downtuned, chunky guitars are the only requirement for "heavy metal", just as technologically advanced special effects constitute an entire "cultural coup" for one of the largest and oldest countries in the world! And it just so happens that it is Miss Bald-ass-arre herself who took note of this revolutionary transformation - she deemed herself Cruiser Aurora for Russian film, no less!

In reality, she is the equivalent of a pimple-faced scrawny International Relations college student, whose uniform includes Fidel's hat, "class war" patches (nevermind that his father is a CEO of a medium-sized corporation) and New Democratic Party pins (Vladimir did not have the luxury of Crest White Strips like Jack!) and a growing collection of Che Guevara t-shirts in various colors, which he proudly wears on his daily trips to Starbucks, where he discusses Hegel or Sudanese torture methods over four-dollar coffees.

He missed the boat, while this misplaced Cruiser Aurora sank even before it fired blanks. Miss Bald-ass-arre's recipe for a cinematic paradigm shift is simple: a foreign "entertaining fantasy film" with "ghostly computer effects" that seems "familiar enough" to your average spoiled North American Attention Deficit Disorder teen - the kind of teen our Starbucks Marxist was two years ago, in fact. She almost makes Bekmambetov sound like the new Eisenstein.

I take that back.

I don't think Miss Bald-ass-arre knows who Eisenstein is.

Furthermore, I don't think Miss Bald-ass-arre knows much about her profession, vocation, calling. She calls Soviet film "stodgy".

STODGY.

Stodgy?!

Stodgy - in stark contrast to the kind of market research-based, substance-lacking, shit-in-a-cookie-cutter eyecandy that the Hollywood machine had been churning out for over thirty years?

Similar computerized eyecandy within Night Watch does place it closer to the filmic ideal described above, but its fantastic story line is too complicated, according to Miss Bald-ass-arre. To quote Canada's recent inept Liberal Party attack ads: "We did not make this up":

"If you’re confused enough by the back-story, then the plot of the film....might not be worth getting into", Miss Bald-ass-arre reassures the viewer. "Night Watch is light on action, something that might disappoint North American audiences", she continues. In other words, if you are too dumb or bored (I am sorry - you have A.D.D.) to follow a 114-minute movie about vampires and their hunters with too few explosions, you may still find it "cool and creative". Then you can prove to all your Starbucks comrades that you are for real - you just saw a foreign film.

A non-stodgy foreign film!

(Shouldn't stodgy films temper your steel character, comrade?)

Naturally, Miss Bald-ass-arre is in possession of vast knowledge regarding the stodgy filmic multitude produced in the Soviet Union over the seventy four years of its existence. She is obviously saving all the examples for the publication of her future revolutionary oeuvre on the "cultural coup" d'état that the Russian "nation is embracing", all thanks to the move towards Hollywood within Night Watch!

I can only guess what type of film qualifies as "stodgy" in the author's misguided view. In the 1980's, for instance, USSR released such movies as Heart of a Dog, Little Vera, Cold Summer of 1953, and Come and See. These highly acclaimed works are widely studied and are available for purchase in large video stores. Of course, Miss Bald-ass-arre must be more informed than successful corporations and university professors.

In the 1970's, we were bombarded with Irony of Fate, Afonja, Kindza-Dza, Twelve Chairs, Stalker, and Solaris. Twelve Chairs inspired Mel Brooks thirty years ago, while Solaris led to the recent Hollywood remake. Evidently, stodgy movies often function in an inspirational capacity. Curiously enough, North American press christined the new Clooney-starred Solaris a remake of a Russian novel and film, shamefully mistaking famed Russian director Andrei Tarkovsky for famed Polish author Stanislaw Lem.

Close enough, they were both from the Eastern Bloc!

Was it you who penned that article too, Miss Bald-ass-arre?

Moving further in reversed chronological direction, in the 1960's the Soviet state filmed the likes of Diamond Arm, Hussar's Ballad, and Lady with a Dog, followed by 1950's Ballad of a Soldier and Carnival Night. The latter along with Diamond Arm remain timeless comedy classics.

Enough, enough! We're almost at the height of stodgy stalinist social realism! Did they even have cameras in the Soviet Union at the time?

Let's ask Starbucks' clientele.

He pulls Fidel's hat over his eyes. His comrades shrug.

Let's tell them. Let's tell her too.

Despite the total devastation of the Great Patriotic War, in the early 1940's and late 1930's, Sergei Eisenstein filmed Alexandre Nevsky and Ivan the Terrible, respectively. Not only do they represent a focal point of basic film studies and can be obtained in remastered DVD format at your local HMV, but they are also frequently shown and viewed on television - if you've been feeling particularly stodgy, that is!

In the 1920's too, Eistenstein struck again with Battleship Potemkin along side Dziga Vertov and his Man with a Movie Camera. Both are consistently considered to be some of the most important films of all time, and their ongoing eighty-year old analysis even crosses over into other disciplines - from the history of photography to various cultural studies.

Is this resume reasonably substantial, Miss Bald-ass-arre?

I do have to disappoint you with the absence of computer effects or video game sequences that the "nation is embracing" as a "cultural coup", although there is a scene with a self-animated film camera in Vertov's project - "cool and creative" enough for the birth of modern cinema? Scholars around the world happen to think so.

Do you?

Regardless of seemingly typical ignorance of an entertainment critic, Night Watch is a somewhat above-average fantasy film created for pure entertainment purposes. It obviously aims for Hollywood, which it achieves by drawing from Lord of the Rings' battle scenes, as Miss Bald-ass-arre correctly notes, countless generic vampire movies, and maybe even Ghostbusters, with a more modest budget, funded by overt Nokia and Nescafe ads throughout. She incorrectly (surprise!) states that Night Watch is inspired by comic books and video games, which may be the case visually, but its literal source is not a comic book, but a novel by Sergei Luk'ianenko.

In addition to technological prowess, Night Watch also features original moments in the style of classic Soviet traditional animation, thematically tied to an actual Soviet cartoon of considerable fame - House Gnome Kuzia, which one of the main characters watches on television.

Therefore despite the attempt to adapt Hollywood to Russian sensibilities, Night Watch does not venture beyond its genre and makes no claims to doing so. It certainly makes no claims to cultural revolutions. We'll leave that to Tarkovsky and Eisenstein.

("We'll leave that to Mao!", our International Relations student begs to differ.)

And we'll leave quality film reviews to someone other than Miss Bald-ass-arre.